Emerging SIDS Discovery Based on a Doctor's Near-Death Experiences Starting at 7 Years Old

Although anecdotal reports may not reveal much about disease causation, this one is special. Astounding and multifaceted, it will take time to reveal the full story.

Updated April 10th, 2025.

New Insights into the Tragic Mystery of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS)

Based on an otherwise healthy 7-year-old boy who survived two worrisome symptoms that plagued him sporadically throughout his childhood and youth, always at night while fast asleep, AND an in-depth literature review that provided extremely compelling support for his unusual symptoms, we appear to have uncovered a new mechanism of spontaneous respiratory arrests in children that could explain sudden unexplained deaths in children (SUDC) and infants (SUDI). He survived and went on to become a doctor, totally unaware at the time of the real reason behind the career choice (another story). I am his physician. The doctor’s doctor.

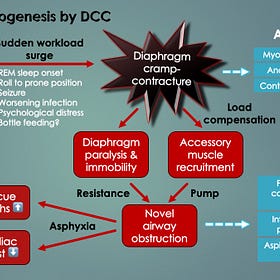

He found himself awakened by a painful bearhug one night, completely unable to breathe in. These symptoms were best described as spontaneous bearhug pain apneas with complete-airway obstruction inspiratory arrest. Clinical (logical) reasoning reduced the differential diagnosis (list of possibilities) to something completely unknown to modern medicine, “novel diaphragm cramp-contracture” (DCC). Diaphragm cramp was thought to cause the pain, whereas an ensuing diaphragm contracture (an effective yet reversible paralysis) caused the respiratory arrest.

He survived by breathing out to breathe in; as simple as that. However, we wondered if an adult could keep cool under pressure like that.

While this bordered on being too good to be true, his account was exceptionally detailed and credible. After all, he was a 52-year-old practicing physician of many years’ experience and a professional reputation to maintain. Also, his recollection of events was consistent each time we pushed for details. Regardless, even if he isn’t believed, the new insights sparking from his account are highly compelling. Enough to warrant further investigation given 8-10 young children are found lifeless in bed each day in Canada and USA combined (from SIDS & SUDC). Professor Paul N. Goldwater MD of Adelaide, Australia, a SIDS guru’s chimed in…

“His [Dr. Gebien’s] hypothesis is congruent with all SIDS risk factors and pathological findings. I heartily endorse his work and his unique SIDS diaphragmatic dysfunction hypothesis.” — Prof. Paul N. Goldwater MD (2024)

See Patient’s Perspective to learn more about his experiences, but first… ⬇️↙️

Other Notables to this Incredible Story

“Astoundingly, thumb-sucking appeared to have spared our young patient’s life [from DCC]”.

Patient 0’s bearhug apnea episodes began only after ceasing his lifelong habit of thumb-sucking at age 7. Indeed, pacifiers (or dummies) lower the risk for SIDS1. We think it’s because of a reduced diaphragm workload, and/or perhaps from a lack of ventilatory pausing at end-expiration (just before the next breath, when cramp is triggered with activation of the muscle).

“One night when 7 or 8 years old while sleeping in bed alone, my mouth woke me up.” — Patient’s Perspective (Patient 0)

Terminal apnea (respiratory arrest) by diaphragm cramp-contracture may not be unique to SIDS or SUDC (older children). It may also be responsible for some seizure deaths as well as sudden cardiac deaths in adults (ones not caused by heart attacks or arrhythmias).

Said cleanly and with minimal angst, this emerging medical discovery appears to be absolutely massive. 😬 [We don’t like making such grandiose statements but it’s the truth and truth trumps discomfort. Also, this is about sleeping babies at risk, clearly something important; knowing we’re doing the right thing (by going public after two years of research and publishing peer-reviewed scientific papers)].

Review of numerous medical case reports, which are not the strongest form of evidence (yet all we have to rely on for now), suggests that many deaths in a variety of diseases and conditions similarly occur by terminal apnea (and not cardiac). In other words, the proximate (nearest) cause of death (and potentially last thing a person ever experiences in this life) could be diaphragm cramp respiratory arrest. [All the more important it is then, to share the counterintuitive rescue breath technique with loved ones: “Breathe out to breathe in!”].

In more detail, upon a comprehensive literature review, death by terminal apnea (potentially from DCC) was also reported in many common life threatening conditions, like severe sepsis (multi-organ failure from blood infections, primarily bacterial), cardiogenic shock (extremely low blood pressure from heart attack, cardiac arrhythmia and severe congestive heart failure) and extreme acidosis, such as diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and severe lactic acidosis (from severe dehydration and hypoxia). In all such cases, terminal apnea deaths were unpredictable, sudden and rapid, consistent with spontaneous diaphragmatic cramp-contracture.

Terminal apneas in fatal seizures may also occur by seizure-induced diaphragm hyperstimulation (via the phrenic nerves, which innervate the diaphragm). Post-seizure lactic acidosis, hypoxemia and compensatory tachypnea all add diaphragmatic ventilatory workload. Along with a postictal (after-seizure) body roll to prone (facedown) position or onset of REM sleep, these could trigger DCC terminal apnea. This might explain sudden unexpected deaths in epilepsy (SUDEP) — another major medical mystery that shares many characteristics with SIDS.

Novel diaphragm cramp-contracture (DCC) is proposed to cause silent respiratory arrests in SIDS and other sudden unexpected deaths

Some of the science behind this new SIDS discovery 🤓

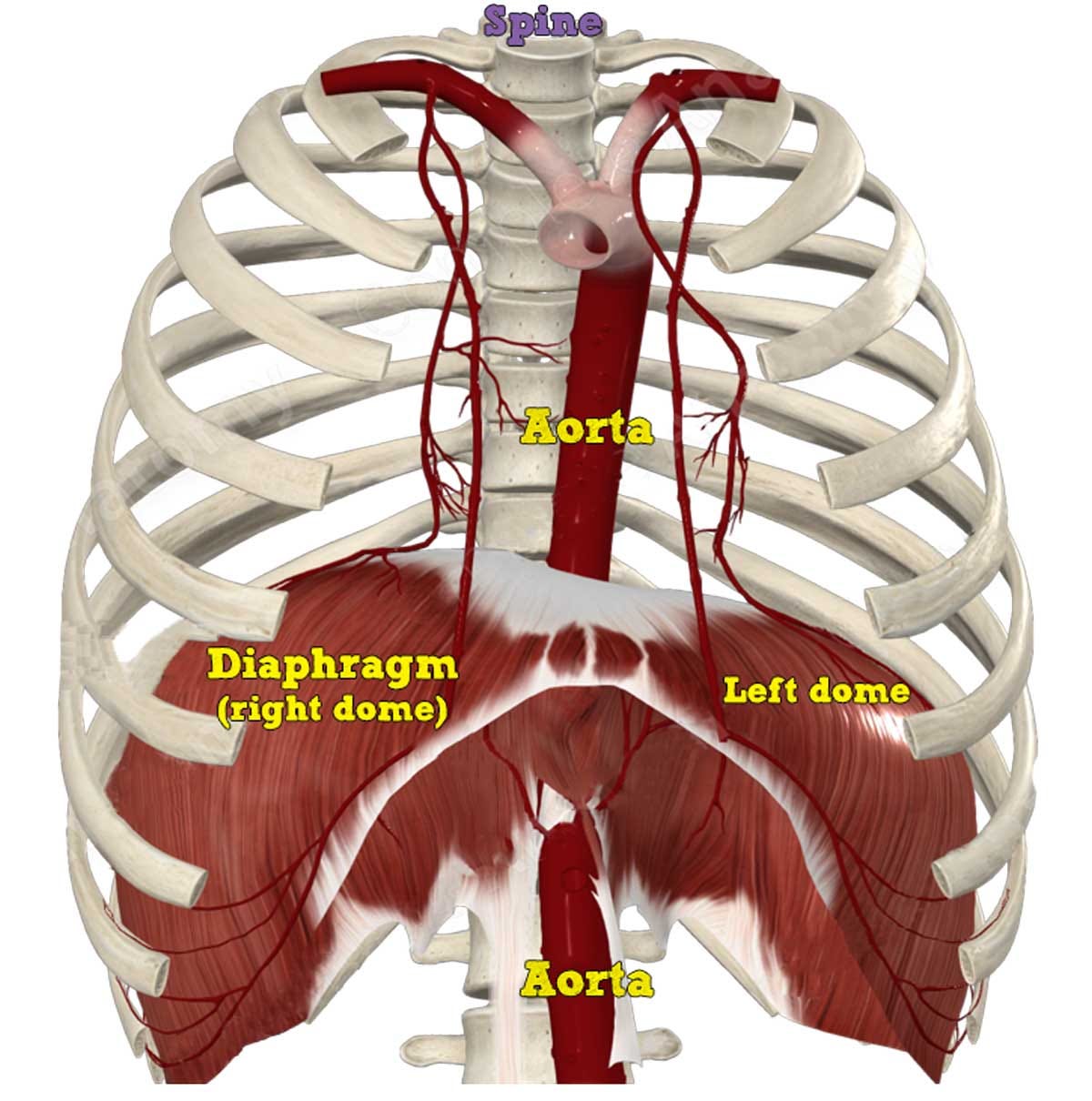

The respiratory diaphragm, a primary inspiratory muscle, separates the chest from abdominal cavity. As it contracts in response to brain (central nervous system, CNS) signals carried by the left and right (bilateral) phrenic nerves, it descends and creates a vacuum, forcing atmospheric air into the lungs. Like the other vital pump, the heart, it is sensitive to oxygen deprivation, carbon dioxide accumulation and an altered acid-base balance of blood (primarily, acidosis).

The respiratory diaphragm, a pump just as vital to life as the heart, needs to be researched in depth. Sudden failure by diaphragm cramp arrest is proposed causal in SIDS and many other types of death. With thanks, to Complete Anatomy.

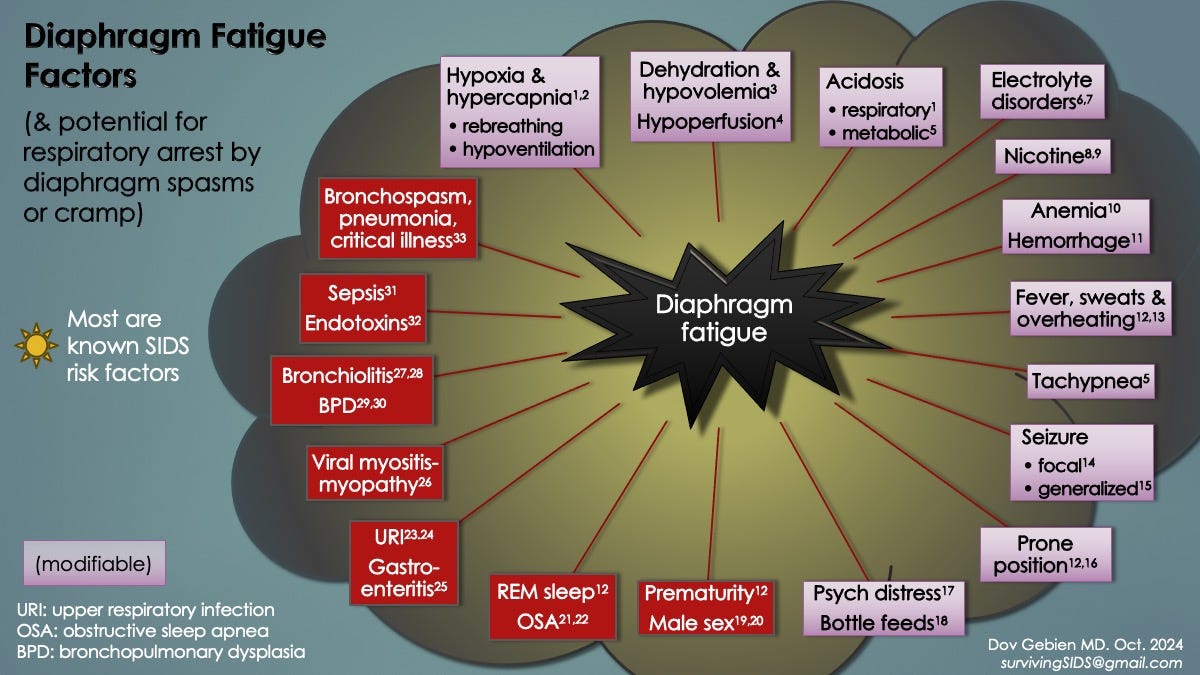

Rebreathing exhaled gases, from pooling in loose bed blankets, bed companions and sleeping prone, disturbs acid-base balance. It leads to hypoxemia (low blood oxygen), elevated carbon dioxide levels (hypercapnia) and high acid levels (respiratory acidosis). All wreak havoc on oxygen-sensitive organs and muscles when the blood buffering system becomes overwhelmed, especially the brain, diaphragm and heart. For example, extreme acidosis lowers the threshold for ventricular fibrillation, a lethal cardiac arrhythmia, causing sudden cardiac arrests2 (probably mediated by altered ion channel conductances). Hypoxemia and hypercapnia both reduce diaphragm contractility and delay its muscle relaxation phase. Both conditions contribute to diaphragm fatigue and novel excitation and is problematic for a number of reasons.

The reduced pump efficiency (or insufficiency) of diaphragm fatigue reduces exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the lungs, leading to further hypoxemia and hypercapnia. A positive feedback cycle ensues, increasing the likelihood of outright organ failure (diaphragm arrest).

When diaphragm relaxation takes longer than the expiration phase of the breathing cycle, incomplete return to resting position occurs. This leads to air trapping (breath stacking) and lung hyperinflation. Ensuing diaphragm thinning reduces its mechanical advantage, thereby contributing to more air trapping and diaphragm fatigue (see #1). Another positive feedback cycle.

When the diaphragm cannot reset itself because of the delayed relaxation, increased muscle tone develops (hypertonicity). As this increases, the organ becomes prone to neuromuscular excitation in the form of twitches (fasciculations), intermittent spasms and sustained contractions (tetanic contractures including novel DCC). Diaphragm myoclonus3 and diaphragm flutter4 are other examples that have been published. At this point, regardless of the brain’s signals to breathe, the diaphragm contracts on its own accord (automaticity). If these contractions are very frequent or inefficient, breathing becomes disrupted and can cease entirely (apnea from diaphragm failure).

When the diaphragm suddenly fails (respiratory arrest), hypoxemia rapidly follows. This leads to syncope (collapse) and sometimes seizures as well as bradycardia (dangerously low heart rate, in children mainly) and then cardiac arrest. In the absence of resuscitative measures, the process leads to a rapid, silent death (only 10 minutes). This is entirely consistent with the sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) as well as sudden unexplained deaths in older children (SUDC) and adults (sudden cardiac deaths, SCD); all of which have plagued humankind ever since walking upright, perhaps earlier.

For science geeks like me, yet written as best as possible in plain English, see:

Companion Guide to "Uncovering Diaphragm Cramp in SIDS and Other Sudden Unexpected deaths"

Original article published in Diagnostics medical journal on October 18, 2024 (doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14202324).

Hints to next article in-progress: Diaphragm fatigue, spasms and cramps in babies

Young babies, especially preterms, are vulnerable to respiratory muscle fatigue.

Increased ventilatory workloads: roll to prone position, REM sleep, bottle feeds.

Diaphragm muscle fatigue + work overload ➡️ diaphragm spasms and cramps ➡️ transient apneas and sustained respiratory arrests, respectively.

Fatigued skeletal muscles become cramp-prone when one is unfit, overheated and dehydrated. In infants, especially ill ones with say a common respiratory viral infection, similar conditions favoring cramp genesis include fluid and electrolyte losses, fever/overheating, rapid breathing,

SIDS is complex and multifactorial. For example, there are numerous well-known risk factors that did not relate so much to one another, or make a lot of sense as to how they contributed to SIDS. But it now appears they center on increased diaphragm fatigue and added workloads. Fortunately, there are ways to reduce these.

How to protect your baby from SIDS

Sneak preview

Ensure gentle bedroom ventilation with open window or fan (prevents rebreathing)

No baby naps on couch or on your chest (rebreathing, overheating, increases diaphragm workload,)

Avoid over-bundling and polar fleece fabrics (overheating & fluid losses)

More available… check out:

New SIDS Prevention Advice from a Researcher MD

Diaphragm fatigue and cramp are central to SIDS and can be prevented.

New SIDS prevention advice by a practicing, licensed medical doctor with a Master’s degree in pathology and over 15 years’ experience working in the emergency department.

Li DK, Willinger M, Petitti DB, Odouli R, Liu L, Hoffman HJ. Use of a dummy (pacifier) during sleep and risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): population based case-control study. BMJ. 2006 Jan 7;332(7532):18-22. PMID: 16339767.

Gerst, P.H., Fleming, W.H., & Malm, J.R. Increased susceptibility of the heart to ventricular fibrillation during metabolic acidosis. Circulation Research, 19 (1966):63–70. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.19.1.63.

Borroni B, Gazzina S, Dono F, Mazzoleni V, Liberini P, Carrarini C, et al. Diaphragmatic myoclonus due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Neurol Sci. 2020 Dec;41(12):3471-3474. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04766-y. Epub 2020 Oct 22. PMID: 33090303; PMCID: PMC7579554.

Phillips JR, Eldridge FL. Respiratory myoclonus (Leeuwenhoek's disease). N Engl J Med. 1973 Dec 27;289(26):1390-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197312272892603. PMID: 4753939.