New SIDS Prevention Advice from a Researcher MD (reducing diaphragm fatigue in infants)

Diaphragm fatigue and cramp are thought to be central in sudden infant death syndrome and can be prevented in 2025

The medical literature evidence supporting critical diaphragm fatigue culminating in a spontaneous diaphragm cramp in SIDS is not compelling. It’s convincing.

New SIDS prevention advice 2025 by a practicing medical doctor with a Master’s degree in pathology (study of disease) and over 15 years’ experience working in the emergency department. Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS, or crib death) can be avoided, above and beyond the improvements by the “Back to Sleep” campaign that started in the 1990s. It centers on the respiratory muscles, the diaphragm more specifically.

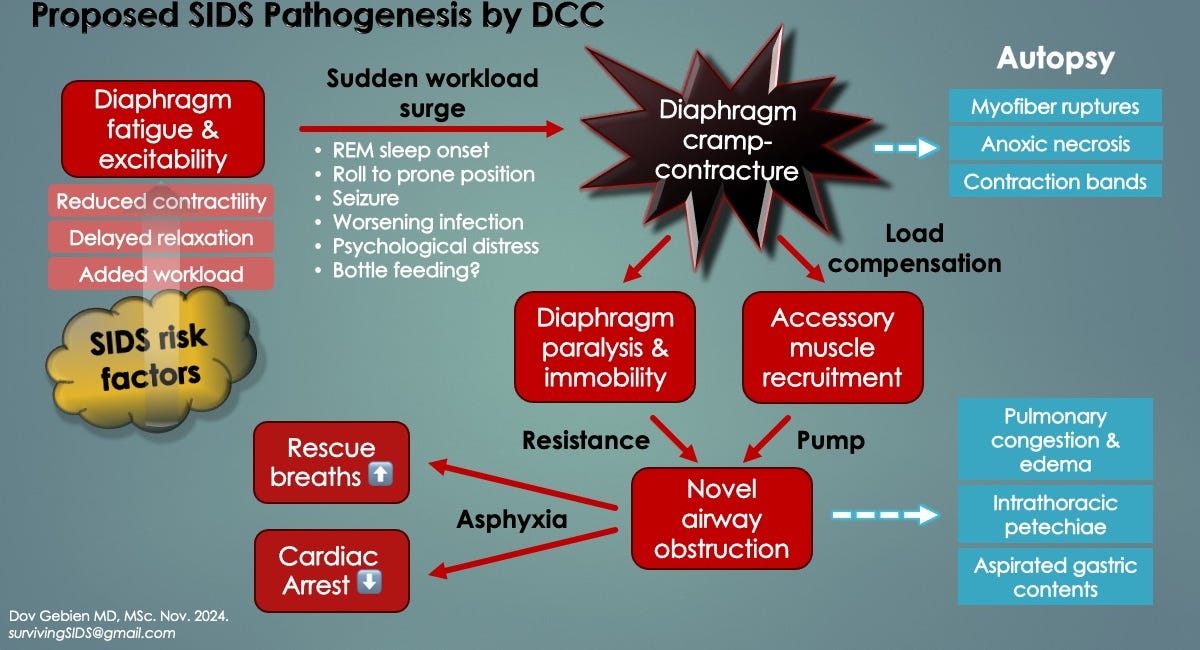

These prevention measures come after two full-time years studying the medical literature in support of a previously unrecognized mechanism of SIDS: novel diaphragm cramp-contracture (DCC). It is thought to shut respiration down in vulnerable infants (those with critical diaphragm fatigue) silently, rapidly and unexpectedly (i.e. no preceding signs of infant distress). Dr. Gebien has published 4 papers on it so far (2024).

Sleep is a particularly risky period for young infants because of respiratory fatigue and REM sleep.

Infants under 4 months of age have underdeveloped respiratory muscles, including the diaphragm and accessory inspiratory muscles, both of which are prone to work overload and failure, particularly in REM sleep. REM sleep places an added workload on the diaphragm because of “tonic inhibition” by the central nervous system. In plain English, to protect us from physically acting out our dreams, the CNS has evolved to shut down (inhibit) skeletal muscles of the limbs and trunk. Unfortunately, this includes the accessory respiratory muscles (intercostals primarily), which normally share ventilatory workload with the diaphragm, but not in REM sleep. A key paper on this, on diaphragm and accessory muscle failure in relation to preterm babies with sleep apneas, is by Lopes et al. (1981).

Diaphragm fatigue has many causes, and it appears they contribute to these “peripheral” apneas (respiratory muscle arrests) in a cumulative manner. If the threshold for muscle excitation becomes exceeded, spontaneous twitches, spasms or diaphragm cramp may occur (DCC, a prolonged spasm). Brief apneas from diaphragm spasms are survivable (despite potential injury from transient hypoxemia), however, serious problems may arise with sustained apneas. These include pallor and cyanotic spells, hypoxic seizures, loss of muscle tone (hypotonia), brief resolved unexplained events (BRUE), loss of consciousness (syncope) and sudden unexpected deaths (SIDS). Sometimes, hypoxemic episodes are clinically silent, yet the potential for injury still occurs, particularly on highly oxidative tissues and organs like the brain and diaphragm itself.

As an example of the cumulative (collective) effect of diaphragm fatiguing factors; nicotine exposure, rebreathing exhaled gases, fevers, overheating and a viral infection affecting the diaphragm in a young male infant (under 4 months’ age) might be enough to tip the balance. Notably, these are all SIDS risk factors (supporting the idea of diaphragm disease in SIDS). We call this the “critical diaphragm fatigue” threshold. All it takes then would be a workload surge, like rolling to prone position (facedown), REM sleep onset or even a bad dream to trigger diaphragm cramp-contracture. Indeed, one of the new SIDS risk factors identified by Dr. Gebien is infant stress (anxiety), whereby a sudden increase in respiratory rate can overload a fatigued diaphragm and triggering it to fail [Southall et al. 1990].

Household stress can be a SIDS trigger, through its effects on the respiratory diaphragm

Other triggers of diaphragm excitation include a body roll to prone position (facedown), worsening infection (from a cold) and possibly, bottle feeding. All increase diaphragm work of breathing.

It is important for parents and other caregivers to learn pediatric CPR

Specifically, in respiratory arrest, to give effective mouth-to-mouth respirations. This means ensuring an adequate air seal as well as observing for chest rise with each rescue breath.

Although it will take time to validate DCC, there is no harm in following these recommendations.

This printable “SIDS prevention measures 2025” PDF can be downloaded and shared. It’s the Best Baby Shower Gift you could ever give. Please help us with our GoFundMe campaign.

Here’s what’s in the PDF (v.4, January 27, 2025):

Diaphragm fatigue and cramp are central to SIDS can be prevented.

No baby naps on a couch or on your chest (avoids rebreathing exhaled gases, overheating and an increased diaphragm workload). All sleeps should be in a crib, with back-to-mattress (reduces diaphragm workload, avoids rebreathing).

Give lots of fluids before all sleeps, especially if baby has night sweats, has a cold/congestion, or is fussy.

Ensure bedroom is gently ventilated with a fan and slightly open window if possible (prevents rebreathing of pooled gases).

Avoid over-bundling and polar fleece fabrics (overheating & dehydration occur, possibly increasing arousal threshold).

No smoking in household (nicotine reduces diaphragm cramp threshold), especially if the infant sleeps upstairs (smoke rises).

Pacifiers and thumb-sucking are SIDS-preventative, so should be encouraged (reduces diaphragm workload).

For fever (or after-vaccination discomfort), give ibuprofen alternated every 4-6 h with Tylenol at full doses (reduces overheating, fluid & electrolyte losses, and possibly, diaphragm inflammation).

Treat asthma/wheezing as directed by your MD. Give puffer(s) before nighttime sleeps.

Avoid startling baby with loud noises, arguments or anything that causes household stress, even disrupted routines. Southall 1990 showed that hypoxemic episodes occurred more often when infants were stressed. [We believe diaphragm spasms were responsible.]

Hiccups, colic or sweats might be a sign of diaphragm fatigue (hiccups are generated by diaphragm spasm). See MD if these become frequent, especially if ill recently or received vaccinations.

Signs of worsening respiratory fatigue include rib retractions (sucking in) and paradoxic breathing. The latter describes when the abdomen moves up and in with each breath instead of bulging down and out. Although subtle rib retractions can be normal, if they are new or associated with paradoxic breathing, hiccups or sweats, see MD immediately.

To help promote this emerging SIDS discovery and support outreach efforts and publication costs, please see https://gofund.me/9e56e291.

To learn more about diaphragm cramp-induced respiratory arrest in vulnerable infants (with critical diaphragm fatigue), see this:

Companion Guide to "Uncovering Diaphragm Cramp in SIDS and Other Sudden Unexpected deaths"

Original article published in Diagnostics medical journal on October 18, 2024 (doi: 10.3390/diagnostics14202324) [1].